Part 1: Winter

Chapter 1

The Painted Stone

It was balancing day again.

Last month, Freja was too heavy by almost two kilograms. This led to her just eating one meal—dinner—for the following 30 days. In these last two days before the balancing, she was in a complete fast.

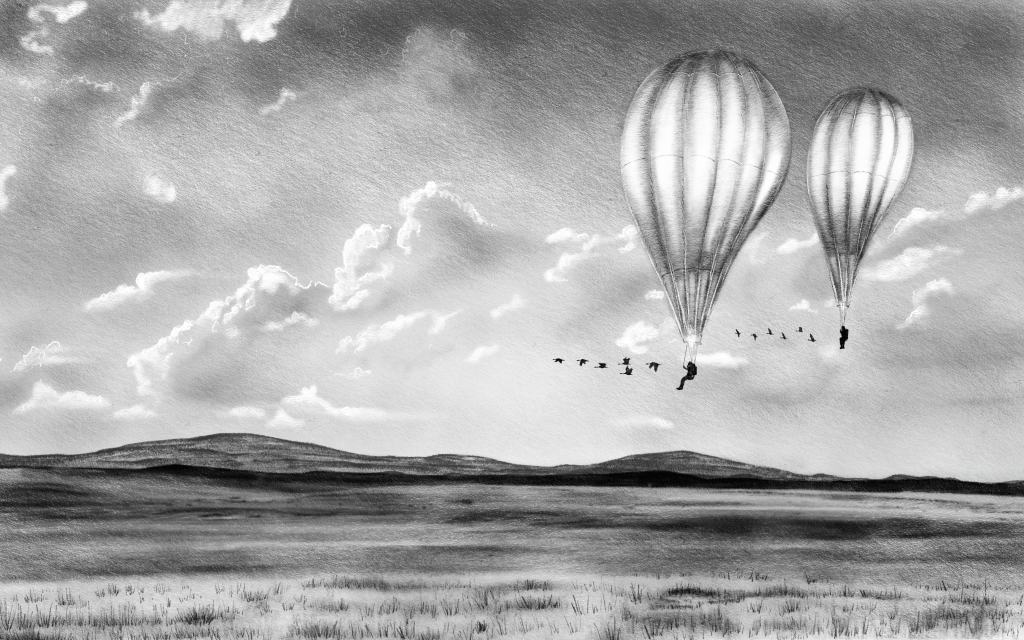

Her empty stomach had awakened her. She crept from her family cell to the edge of BalloonWorld by the fallow, fourth balloon. It was one of the quieter and lonelier places on their crowded, floating platform. Wind whistled through the wooden latticework below in random ghostly pitches like the pipes of a giant organ. Stretching far below this musical weave, a fall of more than 100 meters, was the forbidden, snow-crusted ground.

She had come to this away space of BalloonWorld to cry at first. Then, to think. It’s what they did so well, BalloonWorlders…

Think.

She clutched her knees to her chest to make herself smaller. It was little use. She was taller than every other girl and most every boy too. And still she continued to grow. Auntie Ell, short for her ponderous name Leeuwenhoek, promised Freja she’d be fully grown by her 15th birthday. Auntie Emm, short for her even longer Arabic name, sniffed. She said this girl would go on and on and become a giant.

Freja would have to take matters into her own hands. The truth was probably closer to wretched Auntie Emm’s assessment. If her body refused to stop growing and wouldn’t shed weight, she would have to surrender possessions.

The trouble was BalloonWorlders owned very little. Books were communal in the library. Their clothes were borrowed from central stores—two sets of shirts and pants with socks and underwear, a coat and a sweater rotated out for the seasons. Everyone had the same. Leather and wool flying gear was held by the Quartermaster. The only possessions of difference were in the bag of random items that came with them when they were brought to the platform as children.

Freja clutched the black bag that had come with her from her birth-parents. This was all she had to jettison to meet her weight limit. The bag had an old-style lock, one based on her thumbprint, rather than the more common padlock and key. Fingerprint locks hadn’t been used in a long time, given their taint of technology. Of course, Freja would have to have something different.

Different was not what she wanted.

She pressed her thumb into the square reader and her fingerprint pattern glowed red for a brief second. The latch droned open.

Freja had no memories of her mother or father. Nobody did. Everyone on BalloonWorld was an orphan. Everyone was adopted. For Freja, by Auntie Ell, and latterly by Auntie Emm. These things in her bag were all that connected Freja to a past and a family. She pulled out the first thing she touched. This is what I’ll throw away, she thought.

It was a piece of concrete about the size of her fist. It had been broken off from something, a structure perhaps, smooth on one side where it was painted in a bright swirl of colors. Mostly yellows but there was a swoop of red and line of black through the yellow. The unpainted sides were rough and crumbly. It was one of the more puzzling treasures in her bag. She had no idea what it was but for some reason her mother or father thought it was important that she have it. Was it from an ancestor’s house? Had one of them painted it?

It was dark in her crying place near the fallow balloon but there was always some level of light coming from a gas jet flaring here or there. She held the block up to catch a blush of illumination. She imagined her mother’s hand carefully painting it as a mystery for a daughter she would not see grow up.

It was part of something bigger, that was sure, and it was something a grounder had built. No BalloonWorlder would use stone or concrete given their fixation on weight. Perhaps the location had been important to a great, and great, and on and on grandparent?

The giant san-ge balloon fired, filling its cavernous gut that rose 50 meters up into the darkness. Freja held the concrete rock up in the quickly fading light. She stared at it hard to commit its shape and colors and texture to memory. She closed her eyes to ensure the painted rock persisted in her mind. The swirl of colors was easy to remember, but, for how long? Today, after the balancing, she would draw it on paper and put the drawing in the bag. Of course, the rock was more than any two-dimensional picture could capture. There was the heft of it. The feel of where the rock had been broken off or pried from some bigger construct. She opened her eyes and turned the smooth, painted side towards her. She tried to imagine the rest of the wall that had contained it. A riot of colors and shapes, perhaps as high as they were off the ground. She imagined a huge 40-meter wall painted in a swirl of colors like the aurora, keeping one group safe, another group imprisoned.

Maybe that’s the story or lesson her parents were trying to teach with this artifact. It was a metaphor. A lesson in how to see the whole from a fragment.

She pulled her arm back in a wind-up and threw the rock as far and as hard as she could.

Freja gasped. She hadn’t really meant to do it. She did this all the time, acting and then regretting seconds later. Freja fell back on the thin boards. Fasting had made her weaker and more prone to outbursts.

“Freja, what are you doing child?”

Another gas jet fired—flame surged into the yi-ge balloon—silhouetting Auntie Ell. Freja clutched the bag to herself. The close quarters of BalloonWorld meant few things led to embarrassment; but again, Freja was different, had to be different, and she was ashamed of being discovered.

Freja’s hand anxiously slipped into the bag and came out with the pair of golden scissors. She held them up, the metal glinting in the fading flame of the massive gas jet.

Auntie Ell and the girl looked at this new, sharp tool.

“I was going to cut my hair. For weight,” Freja said.

Auntie Ell crouched down and hugged the girl.

“Freja, every girl cuts her own hair once in her life. And only once.” She put her hand through Freja’s dark, curly hair. She pulled back her own hood and mimicked running her fingers over her own bare scalp. “Your hair is beautiful Freja. Like you. You are a beautiful girl.”

Auntie Ell could tell the girl did not believe her. She held out her hand for the scissors.

Freja was reluctant to give them. They were another artifact from an unknown past. She pointed to the handle. “They’re the gift from Maggie,” she said. Auntie Ell knelt closer to look at the inscription.

“Gift of the Ma-Jie,” Auntie Ell said. “Grounders pronounce M-A-G-I as Mă-Jī. A soft G and a long I.”

“What’s a Ma-Jie?”

“It’s an ancient term for holy people or teachers. Story writers also use it as a name for magicians.”

“The scissors are magical?”

Auntie Ell laughed. “There is no such thing as magic. The world cleaves to stark and definite laws, my child. As you know.”

“I thought, perhaps, it was the name of my mother—Maggie. It’s a grounder name for females, isn’t it?”

“It is. And who knows my child? There is so much we no longer know.”

Freja nodded. That was an inescapable truth.

“Let’s cut it,” Freja said.

Auntie Ell was talented with hair. As she passed Freja’s curls through her fingers, Auntie Ell thought the girl’s hair felt like a grounder’s. Softer, moister, fuller. Up here, in the constant wind of BalloonWorld, hair was short and dry and brittle. Freja’s was different.

There was a truth. Freja was different.

When she finished, Freja’s curls closely framed her. With a pang, Auntie Ell thought the girl now looked older.

“You are beautiful. I know beauty does not matter. Does not matter at all. It doesn’t matter to me.” She laughed at herself. At her bristly scalp. “You should sleep before the balancing. It will help,” Auntie Ell said and stood up, reaching a hand down to Freja.

“Wait. I’ve been saving food for them.” Freja pointed far down to the ground below them. The frosted tips of the great grasslands were invisible in the darkness, like the bottom of the ocean.

Auntie Ell followed Freja to the edge of the platform and stared over the fencing and into the shadow.

“There are dogs below us,” Freja said. “Do you know dogs?”

Auntie Ell nodded. She had seen pictures of the animals in books.

They stood at the brink of BalloonWorld. Freja took a package from inside her quilted coat. “Fish skins,” she told Auntie Ell. The black, mottled skins were rolled tightly. Their smell made Freja’s hungry mouth water. But Freja dropped them, one by one, like secret messages, to the plains below. A few seconds later with the inevitability of gravity, they heard yelping and barking.

“The dogs have been coming here all this past month, just like me, after I failed my balancing. I was saving food, in case, but then decided to give it to them. They listen to me.”

Ell couldn’t help herself and embraced the girl. She held her for longer than she normally would. Freja accepted it as a sign of love.

But Auntie Ell was thinking something else. She wanted to warn this strange child but then didn’t want to unsettle her today any more than she already was.

Truth was their kind—BalloonWorlders, the people imprisoned in the sky—did not make friends with creatures of the earth.

Chapter 2

The LightHouse

Across the frozen-tipped grass Thomas heard the dogs barking. His shutters had blown open; the LightHouse keeper had again failed to fix the latch.

Cold air blew in from the plains and with it, the distant, excited yelping. Thomas sat up in his bed, clutching the wool blanket more tightly.

Wearing it about him as a cape, he walked over to the open window and looked out. And up. Invariably, his eyes were tugged upwards towards the giant barge.

At night, you didn’t see this huge thing floating in the air so much as you were unsettled by the absence of stars it blotted from the sky. Then there was…he waited…on a cold night the fires would be more frequent…WHOOSH

A gas jet lit a column of fire up into a towering balloon.

Immediately, the barge became visible in the sky. A platform the size of a playing field, hanging more than 300 feet up off the ground. The balloon warmed and glowed with the fire inside of it. That’s when you got the sense of their size. Each of the three working balloons rose another 150 or more feet off the platform, swelling to spheres at least 100 feet across. Thomas had been at this outpost for almost one month and had not yet lost his wonder of them.

The balloon that had just fired and now after-glowed was the Two-Snake balloon. He named it for the criss-cross serpentine S’s with lines connecting the curves of the letters. Two-Snake balloon was on what Thomas considered the stern of the barge, if the barge were ever to sail away from the LightHouse. Of course, that would never happen. The barge was tethered to the precious gas line that fed its burners and balloons, and the gas line was managed by the LightHouse.

The other balloons had different symbols. He had seen them all when the dogs, the cold, or bad dreams woke him up at night.

Why the balloons needed warning symbols seemed a bit much. If you didn’t know enough to stay away from people forced to live on a floating wooden platform in the sky, you were pretty stupid.

“They’re the descendants of people too smart for their own good,” the LightHouse Keeper said. It was one of the few times he spoke words, and more than one at a time, rather than grunting or pointing out what needed to be done with a flick of his head.

The dogs had stopped barking.

Thomas closed and tried to lock the shutters but knew the latch would give. He returned to his bed, curling himself into a ball for warmth. He reached under the bed frame for the cap his mother had knit. She must have known it would be colder out here at a LightHouse than the warm house he had to leave. She didn’t blame his father for this calamity even though it was his doing. The laws were plain that the sins of the father were visited on the son and daughter, and on and on. The bargers up there were proof of that law. Thomas didn’t know what his father had done to warrant his removal as well as Thomas’s. His mother would not tell.

She was a good mother. He was a good father. Thomas shut his eyes and pictured his father’s face. The last time he saw him, well before Thomas boarded the ship to cross the Great Lake, his father looked bad. He had a scraggle beard. His hair was long and unwashed. Thomas’ prior memories of him were as a clean-shaven man, with a lemony-spice smell from the soap he used for shaving. Not the raggedy man allowed to see them for a two-day furlough from his forced work fighting the tundra fires. Still, his eyes had been the same. Rather than being ashamed of his appearance and turning away, his father let Thomas stare and take him all in. Thomas saw it, deep in his eyes, the same sense of wonder that had illuminated his father before.

It was the same eyes of the father who had read Aesop’s fables to Thomas every night.

The sour grapes.

The dog and its reflection.

Mercury and the golden ax.

Thomas shivered even with the woollen hat. Tian-hao, it was still cold. He pulled the toque down more tightly.

WHOOSH…Fire surged far above him.

The descendants of people too smart for their own good. The boy who froze in bed. Thomas remembered the fable of the rabbits and the frogs.

The rabbits were frightened of everything. They were chased by foxes. By crows. By dogs. Finally, the rabbits declared there was no point continuing to live. If everything in the world was against you, if every creature hunted you, if you were afraid of everything that moved, you might as well end it all. The leader of the rabbits led her pack towards a river in the middle of the night. It was resolved they would all rush down the hill and into the water to drown themselves. They counted…one… two… three… and then all the rabbits hopped madly down the hill. As they stampeded to the riverbank, a community of frogs who lived next to the water suddenly made a great noise and leaped into the water, frightened for their lives. The rabbits stopped, surprised at the commotion. The leader held up her paw and led the rabbits back up the hill. They waited. The frogs, hearing no more noise, returned to the riverbank. She pointed with her paw and the gang of rabbits charged the river, and again the frogs bolted into the water, scared out of their wits.

The rabbits halted. This was a new development.

Perhaps the world was not such an awful place. Or rather, perhaps they were not the ones in the most awful predicament.

And so, the rabbits decided to live at the top of the hill, in sight of the riverbank and the community of frogs who, on full moon nights, they could watch, seeing the reflected glow from their bulbous eyes staring warily up the hill. Up there, to the bewildered and beleaguered frogs, were creatures who hopped like them, but who charged them, striking terror in their tiny frog hearts whenever they chose.

WHOOSH…Another gas jet ignited, filling another balloon to hold the barge in the air.

The shutter blew open. Thomas could see the barge’s flame was dimmer, coming from the bow and blocked by the other balloons. Even with the noise of the gas jets and the cold and the pang of memories, Thomas was finding his way back to sleep.

I’m cold but I’m safe on the ground. The bargers were his frogs, Thomas thought as he drifted off.

I am their rabbit.

Chapter 3

Waiting to Balance

Freja opened her eyes to Euler standing in front of her. Euler tall and beautiful, rumpled in a grey baggy long coat draping over his skinny frame.

After cutting her hair she had returned with Auntie Ell to their cell and climbed into her hammock. Anxiousness and hunger held her awake. Freja slid down from her bed with the grace of an acrobat, gliding through the narrow canvas corridors of BalloonWorld to wait in the cafeteria.

Euler was blocking Freja’s view of the Libra and her boys as they set up the balance. Edison (hateful Edison) and Faraday had unpacked the apparatus while Freja slept. They were assembling the stand and lever arm across it.

“I like your hair,” Euler said.

Despite Euler’s efforts to distract her she could see the pieces of the scale wrapped lovingly in white clothes as if they were cherished heirlooms. The two boys from the Libra’s cell would next build the separate pieces of the human-sized, two-pan scale. Later this morning Freja would step on one of the plates. Freja scowled. The balance was an implement of torture, made worse by being handled by Edison. Edison was her age and second tallest of their cohort, after Freja, of course. If Freja felt she was destined to be different, Edison felt he was destined to lead.

Edison thought of himself as an irresistible force. Freja knew she was an immovable object.

Sensing the bile that rose in Freja from the sight of Edison, Euler came closer and put his hand on her head, running it through her hair, as if to cool her anger. He was one of the few who could break her shield and touch her.

“You have so much curl, I didn’t know.”

“I know what you’re doing,” she said.

“But I don’t know what you’re doing. Sitting here in full sight of the balance. And Edison. Why do that to yourself?” Euler said.

Euler had his welcome smile on his beautiful face. It lifted the strangled heart of her empty body.

He returned to her hair. “It’s so…forward. So direct,” he said.

Such an Euler compliment. Freja’s nerves and hunger made speaking difficult.

He touched her forehead. “You’ll be fine. I can tell by looking at you. What was it last time, one kilo?”

“Almost two. One-point-nine kilograms. Nearly two textbooks,” Freja said. Euler would remember the exact amount. His memory was prodigious. Like his intellect. Edison only won contests of intelligence that Euler decided to lose.

“Easy,” Euler said.

“Easy for you to say. You’re half bird. I’m sure you have hollow bones,” Freja said. Euler, though the same age as Edison and Freja, was considerably slighter. He looked two or three years younger, until his eyes met yours. Their intelligence, their wisdom—they made him seem ageless and in a way, from another world.

“Don’t they balance the san-ge order first today?”

Freja nodded.

“And you’re in the si-ge. Why sit through all this preparation and then 15 weighings that don’t matter to you?” He held out his hand to lead her.

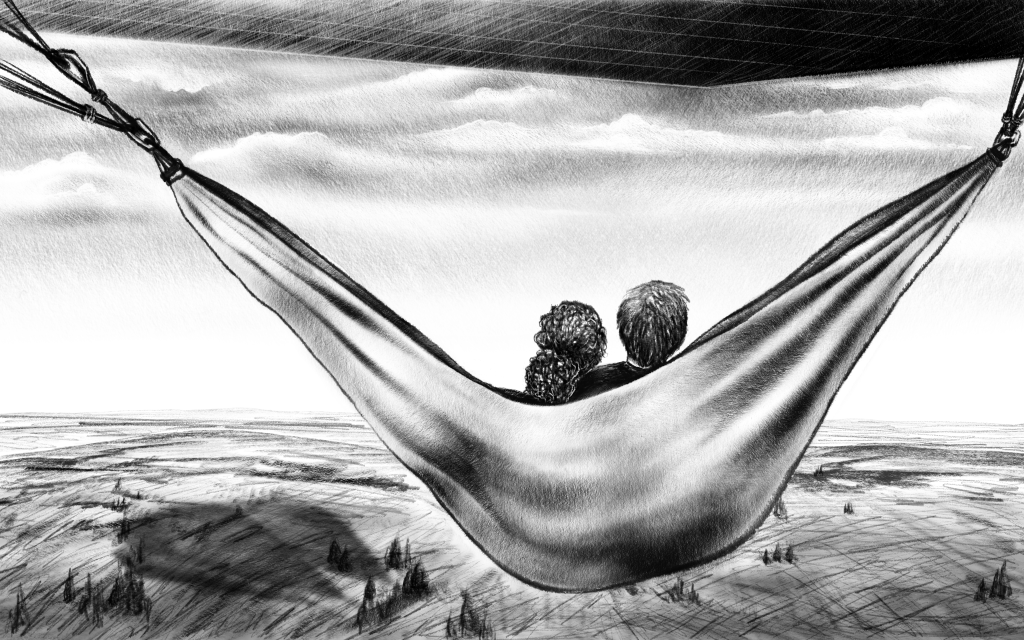

They left the cafeteria, ducking along corridors and slipping through canvas walls to the yi-ge balloon’s engine room. One person was working the gas line. Such was Euler’s influence that she simply nodded at him to let him through. He pulled the canvas curtain across and latched it behind him. Freja thought they were going to climb the balloon, perhaps to the Crow’s Nest. Instead, Euler crouched down and lifted a floor panel. Underneath, Freja saw the wooden substructure of the platform that she had heard whistling earlier in the morning. Through the gaps in the struts and boards, now that it was daylight, she could see the grey shadow of the earth below.

“Few people go below,” Euler said. “But it’s safe. I’ve done the calculations—all of this is supported. Planks and beams we didn’t absolutely need are excess weight. They were stripped away years ago.”

He bent down and lowered himself under the floor and disappeared. Venturing below their surface, into the hold if this were a ship, was something BalloonWorlders did not do. They didn’t like to be reminded they were so distant from the surface. This was something then, that a girl like Freja would do. A misfit. Someone who didn’t belong. Euler was a conundrum. He belonged so much that he was an un-named part of council but then at the same time he did not belong with any of them at all.

This was likely their attraction. She slipped under the platform to the lattice world below.

Euler was crawling along inside the beneath of BalloonWorld. There were gaps among the angled boards and struts like tunnels. If you slipped, you’d likely bring up on a set of planks below. If you were unlucky you’d slip through them all like a bird escaping a net. The sun had crested the plains’ horizon and shone up to their floating home. BalloonWorld’s shadow would be cut into clouds above them. Euler climb-crawled along sure-footedly. It was obvious that he had been here many times before. Freja followed him through the tunnel-maze until he led them to a canvas hammock attached by four points to the platform above. Next to the hammock he had affixed a supply bag. A safety mesh hung underneath the bag and hammock. Euler crawled inside the hammock and motioned for her to come in.

Freja looked at the tie points of the hammock. They were double-grommeted and triple tied—each of them. Euler would have done the calculations. She crawled her way over to the hammock through the lattice.

She fell into the hammock pressed up against Euler. The hammock swayed with the addition of her body. She froze.

“Do you know comic books?” Euler asked.

It was hard to concentrate on his question while the hammock was moving so much. It was bigger than a single, like the one she slept in, but not by much. Euler put his arm around for the sake of space.

“Comic books?” he repeated.”

“If it’s what I think, we have some in the library. Stories with pictures and words,” Freja said. “People have bubbles above their heads, like quotes in novels.”

“Do you know the comic book Superman?”

Freja shook her head.

“Superman was a popular comic. A handsome man from a faraway planet and his planet was destroyed. His parents put him in a ship alone, sending him to earth to save him.”

“He’s an orphan,” Freja said.

“Like us,” Euler said. “Superman has amazing powers, apparently because he grew up in the energy field of a star different than our sun. He can fly. He has super-strength. His eyes can shoot lasers.”

“We fly but I don’t think we have super-powers,” Freja said. “Laser eyes don’t make sense from the influence of a star.”

“Comics were not based on science. BalloonWorlders are a much more challenging audience than old-world Grounders. Here’s why I like Superman. He had a special place. He was always working on plans to save people or the world. He needed somewhere to rest. To repair. He called it the Fortress of Solitude.”

“Your rest place after saving the people or the world,” Freja said.

“I’m working on it. We need to be more than the Libra, the QuarterMaster, the Pilot and the Judas. That’s Grounders defining us.”

“We need to stop being weighed every month,” Freja said. “Maybe you could stop that.”

“I will stop that,” Euler said.

How would Euler stop that, she wondered. He was just trying to cheer her up. As long as they lived on BalloonWorld, they would need the gas-line and its fuel to fire their giant balloons that kept them up, off the earth.

“I understand why I might need a Fortress of Solitude. I am too big. I am too different. I don’t fit. I’ve been going to the fallow balloon edges this whole month to cry in despair. You are the youngest member of council. You are the smartest person on BalloonWorld. Why do you need to come here?”

“We all have different ways of not fitting in Freja,” Euler said.

“You are too perfect to not fit in, Euler,” she said. She leaned into his spare body and felt its warmth. She was in a safe place even if she was hanging in a fabric hammock over 100 meters above the earth. She felt that it—everything—would work out. She looked up at his beautiful face. She was understood. She was accepted.

She put her cheek on his chest and despite the threats of falling and balancing, within a minute or two, fell fast asleep high above the ground that longed to kill them.

Email the author: jblackmore.writer@gmail.com